Some more background is beginning to emerge on how the Home Office plans to implement the Communications Data Bill as and when it finally becomes law. And it’s looking like it could be a PR disaster for the government.

For those that don’t already know about it, the CDB is intended to give the police and security agencies essentially the same ability to monitor Internet-based communication, such as email, that they already have over our telephone conversations. I blogged about it a couple of weeks ago, giving my initial reactions to the proposals.

Extending monitoring powers to the Internet isn’t necessarily hugely controversial, although the civil liberties lobby is, unsurprisingly, opposed. The police have always had the ability to find out, if they want to, who you are making phone calls to and receiving them from, so it’s not a big stretch to want to extend that to knowing who you email and who emails you.

The problem, as always, is in the detail. My initial thoughts on the Bill was that parts of it were well-meaning but misguided, and that it was likely to prove impossible to fully put into practice. The main problem is that getting details of Internet-based communication is extremely difficult. I originally thought that the Bill’s backers simply hadn’t thought of that, or that their expected solutions wouldn’t work. It seems I was wrong. Not only have they thought of it, they’ve come up with a solution to it that gives them the ability to spy on absolutely everything you do online, including accessing your online banking, using Facebook, downloading porn and playing online games.

Getting records of telephone calls is easy, because the telephone companies have to keep them in order to charge you. If you have an itemised bill, then you get to see a copy of those records yourselves. It’s no big deal for the police to get a court order requiring the phone company to hand them over to them as well.

With email, though, it’s not so easy. If you have an ISP-issued email address (say, your.name@talktalk.com) then they will have logs of when you send and receive email through their system as well as where those messages are going. But if you use a webmail account (say, your.name@hotmail.co.uk or your.name@gmail.com) then they won’t. Monitoring that can be evaded just by setting up a webmail account is clearly useless, since anyone planning to discuss nefarious deeds by email will simply do just that.

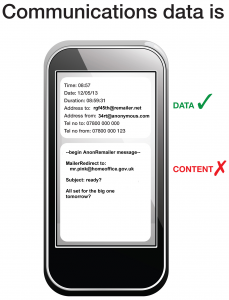

This is where it gets a bit more complicated. The Home Office says it doesn’t want to store the content of emails, just the “data” – that is, details of who it is sent from and to (just like your itemised phone bill). With webmail, though, the email data is sent as part of the content of the web page. The distinction between data and content is, on the Internet, almost entirely arbitrary. So to extract the data means first taking all the content, then distinguishing between the content that is actually data and the content that really is content, and only storing the former.

That’s not too hard, and it’s the sort of thing which can easily be automated. But it also means that the Home Office computer has to inspect all the content of every webmail even if it doesn’t keep it. It’s easy to see that there’s only a small step from there to actually storing it, which is partly why the civil libertarians are concerned.

That’s not the half of it, though. Separating webmail data from content is easy if you can obtain it and read it. And obtaining it is very easy – so easy that it’s a simple party trick to be able to tell people in your home or office what web pages they’ve been viewing with the aid of some freely downloadable software. (It isn’t just for spying on people or playing practical jokes; this software is a key tool for diagnosing network faults, which is precisely why it’s widely available and routinely used by Internet professionals).

But most webmail services now routinely use encryption to protect the content, for that very reason – people want to be sure that their emails aren’t going to read by colleagues, family members or ISP engineers as well as those who want to read them for potentially criminal purposes, such as identity theft. So to be able to read the web page content and extract the email data from it, the Home Office computer is going to have to decrypt the content first.

That is where it gets really, really tricky. Because, of course, the whole point of encryption is to prevent unauthorised people decrypting it. The technology used by Gmail, Hotmail et al is exactly the same technology used by your bank to secure your online banking page, and by credit card companies to secure online card transactions. It is designed to be hard to break. It is designed to be too hard even for governments to break.

It’s not impossible, of course. There are at least two ways of getting at encrypted content, at least in theory. Only one of them is known to work in practice. It’s not impossible that GCHQ has come up with some previously unknown and unpublicised means of doing it, but if they have then it’s such a stupendous advance on everything currently known to exist that I doubt they’d risk letting on by using it in this kind of situation. So if the Home Office is going to decrypt webmail communications, then it’s almost certainly planning to do it using the tool which is already known to work. Incidentally, if the Home Office has the ability to decrypt your webmail then they also have the ability to decrypt your access to any other encrypted website, including your online banking and your credit card usage. Fanciful, maybe, but it’s worth noting that HMRC are one of the organisations that will have access to this data.

That tool is what’s known in Internet jargon as a “Man in the Middle” attack. I really don’t have space to explain in detail how it works, but in essence it’s quite simple. If computer A (your home PC, maybe) is communicating with computer B (Gmail’s website, say), then another computer, C (the Home Office snooper), can intercept the traffic by pretending to A to be B and pretending to B to be A. In effect, A and B both think they are talking to each other, whereas they’re both actually talking to C who intercepts the message and passes it on. That gets around encryption, because both A and B can then be tricked into using an encryption code which can be decoded by C instead of one which only they can decode.

The problem is that it still isn’t that easy. If it was, then criminals and hackers would already routinely be using it, and encryption would be worthless. The defence against it is for A, when talking to B, to only accept an encryption code that it knows to be trustworthy. If it isn’t, then it tells you so. You can see that in action if you try to go to my own website using an encrypted connection – your browser will warn you not to proceed. In this case, it is safe, as the only reason the encryption is untrusted is because I just made it up instead of using a trusted source. But if you got that warning when you visited Gmail, or your banking website, then you would know something is amiss.

This is the crucial point, and I apologise for taking so long to reach it. The Home Office can’t intercept and decrypt your encrypted Internet communications without triggering all these warnings unless it manages to insert its own computers into the chain of trust. There are ways of doing that, but all of them would require either the cooperation of every computer manufacturer and every browser software supplier in the world or the cooperation of all the global organisations which are responsible for system of trust itself. It would be very difficult to do either, and even harder to do it without it becoming known. The alternative is to make everyone in the UK put up with the browser warnings when they want to use their webmail.

I can’t see either of those working in practice. There are other issues too, not least the fact that a Man in the Middle attack invariably slows down the connection because every piece of data has to be transferred twice and encrypted/decrypted twice. And, if you know it’s happening, there are measures you can take to avoid it.

However, the Home Office seems bent on pursuing this course, probably in the hope that by the time it comes to implement it the technology to do so undetectably will have been developed. I think that’s a vain hope, and so does everyone I’ve spoken to in the Internet industry.

What’s more likely is that this will turn into a long drawn out car crash for the coalition as the public gradually begins to understand the implications of the proposals. These proposals have all the hallmarks of having been inserted into the Bill by power-hungry civil servants eager to take advantage of the average MP’s (and average minister’s) lack of in-depth technical knowledge. But failing to understand it could be disastrous for ministers and their advisors. Internet snooping has the potential to be just as toxic for this administration as ID cards were for the last.